Understanding Arcpy

by The Dukes of Hazards

2020-03-14

The tutorial provided here is originally published by The Dukes of Hazards consulting team, Spring 2020 (see here), and is reprinted here with permission.

ArcPy

What is it???

Well, it’s a Python package, a.k.a. a library, a.k.a. a collection of structures and premade methods that make it easier to use Python for geospatial applications. Python is already a pretty commonly used general-purpose language, and it’s especially suited to big-data applications, so working with spatial data is just a natural extension of what Python is already good at. The advantage of ArcPy is that it allows us to go under the hood and create our own “Tools” for use in Arc’s “Toolboxes”. Or we can just bypass Arc entirely and run the tools straight from Python! The beauty of programming is in its versatility.

Getting Started

Okay, so every programmer knows that the worst way to write anything is just to open up your handy-dandy, trusty-rusty text editor and start plonking down code into that little keyboard of yours. The syntax of programming languages, library functions, and methods are just too specific and complicated to memorize well enough that you get it perfect on your first try. Plus, when you write a huge thing and then realize it’s broken, it’s a lot harder to find the broken part than if you just write something small that’s broken. Assuming that our first try will be wrong, let’s use ArcPro’s built-in Python shell, which you can find by clicking “Python” under the Analysis tab, to test everything we do on a really granular level before we throw it to the dogs. If you want to follow along, have a look at this script by Dr. Davis.

The first thing we need to do is load in the project and set up where our data are coming and going from. arcpy is available by default, but we should also import os before we do anything.

# Setting up my folders

aprx = arcpy.mp.ArcGISProject("CURRENT")

base_dir = os.path.dirname(aprx.filePath)

out_dir = os.path.join(base_dir, "Output")This is pretty self-explanatory. The first line is a constructor for an ArcGISProject class. Classes are the “objects” of object-oriented programming; they allow programmers to represent structures and perform operations on them in a way that can be extended to many different instances of a single type of structure, or more specific versions of that structure. The important thing to understand here is that now your code has set aside space to store an ArcGISProject and filled it with a class representing the current project. We are also using OS functions to get directory names and file paths. This is because different operating systems have different naming schemes for their file paths, so rather than try and make something that works for everyone, we’ll defer to the OS and let it handle file paths the way it wants to. Our output directory will be set to a subdirectory of the base directory called Output.

# Define constants

k_pi = 3.14159

gamma_r_nm3 = 20000.0 # unit weight of soil, N/m3

gamma_w_nm3 = 10000.0 # unit weight of water, N/m3

# Define input rasters

lands_h = "soilmu_a_aoi_utm_h" # depth of regolith, m

lands_phi = "soilmu_a_aoi_utm_psi" # internal friction angle, deg

lands_c = "soilmu_a_aoi_utm_c" # soil cohesion, Pa

lands_theta = "collbran_slope" # hillslope angle, deg

# Define input water depth, m

water_h = .2Here we create variables to store our constants (which are needed for the equation) and the names of our inputs. In Dr. Davis’s case, these were datasets about Collbran, CO, but obviously that’s only for this application. We’re storing these input names in variables so that, when we turn this into a toolbox, we can easily fill those variables with whatever inputs the user provides without having to rewrite any code. We’re anticipating portability from the outset!

# Create radian version of slope

theta_rad = arcpy.sa.Times(lands_theta, k_pi/180.0)

phi_rad = arcpy.sa.Times(lands_psi, k_pi/180.0)What we’re doing here is converting our slope and internal friction angle rasters from degrees to radians, because our model uses those darn trig functions, which are built into Arc (👍), but only take radians (👎). Remember that we defined k_pi above as a truncated version of pi. π radians is 180 degrees, so we can just do lands_theta = lands_theta * k_pi/180, right?

WRONG!

lands_theta is just a text string containing the name of our raster, and we can’t multiply that by any floating-point numbers anyway. We need to multiply every cell of these rasters by k_pi/180, and for that, we must defer to the arcpy.sa.Times function. It’s verbose, but what can you do.

Notice that we’re not overwriting lands_theta and lands_psi with these operations; we’re instead storing them in brand new variables. This is just so we can keep the old rasters just in case we need them for something. Even if we overwrote lands_theta and lands_psi, the rasters themselves would stay anyway, since those variables only contain their names.

Now it’s time to throw all this crap in the critical rainfall threshold model. Dr. Davis has written it out nicely for us.

\[ F_s = \frac{\tan \phi}{\tan \theta} + \frac{C}{\gamma_r * H * \sin \theta * \cos \theta} - \frac{\psi_t * \gamma_w * \tan \phi}{\gamma_r * H * \sin \theta * \cos \theta} \]

or

\[ F_s = F_f + F_c + F_w \]

As you can see above, he’s dubbed the three fractions Ff, Fc, and Fw. It’ll be easier for us to calculate those three on their own first and then put them into the final equation. Let’s start things out easy with Ff.

# STEP - Calculate Ff

ff = arcpy.sa.Divide(arcpy.sa.Tan(phi_rad), arcpy.sa.Tan(theta_rad))Ff is the simplest one. As I said above, since we’re doing calculations on geospatial datasets, the division sign isn’t going to do what we want here, so we have to call some built-in ArcPy functions. Luckily, they already have everything we need built-in so it’s really not too bad.

# STEP - Calculate FcHere, things start to get crazy. Let’s go line by line.

sin_cos = arcpy.sa.Times(arcpy.sa.Sin(theta_rad), arcpy.sa.Cos(theta_rad))What we’re doing here is making the (sin θ) * (cos θ) part of the equation. It appears in both Fc and Fw, so making it its own thing now will help us down the line too.

# Soil depth vertical (influenced by gravity)

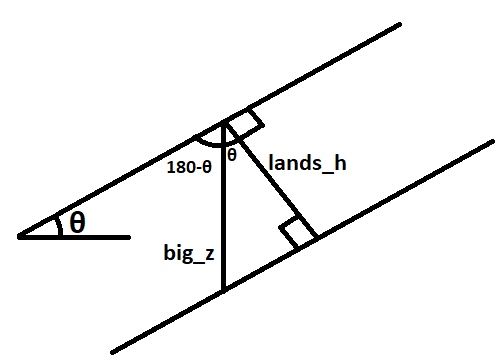

big_z = arcpy.sa.Divide(lands_h, arcpy.sa.Cos(theta_rad))We need to calculate the vertical soil depth here. The soil depth measured from our raster is the distance from the soil surface to the bedrock, but the problem is that it’s measured perpendicular to the slope of the surface. This is fine if we’re working with totally flat land, since perpendicular to that would just be straight down, but we’re not. So, since we already have all the slopes, we can use cosine to get the vertical slope. If that explanation wasn’t sufficient, check out this diagram.

Figure. Diagram showing regolith surface, bedrock surface, measured height and slope angle for getting vertical height.

h_sin_cos = arcpy.sa.Times(big_z, sin_cos)

c_gr = arcpy.sa.Divide(lands_c, gamma_r_nm3)

fc = arcpy.sa.Divide(c_gr, h_sin_cos)Now we’re back into the simple stuff. We multiply our new H by sin_cos to get H * (sin θ) * (cos θ) and store it in h_sin_cos. Then we do the C / γr portion of the equation, store it in c_gr, and then divide h_sin_cos by c_gr to get Fc.

We’re in the home stretch! Time to do do Fw.

# Step - Calculate Fw

# Pressure head parallel to hillslope

ls_psit = arcpy.sa.Times(water_h, arcpy.sa.Cos(theta_rad))It’s time to calculate ψt. To do this, we have to do something similar to what we did before. We need the water pressure head parallel to the hillslope, so we get that by multiplying the cosine of the slope by the depth to water.

g_wr = gamma_w_nm3/gamma_r_nm3

pgwr = arcpy.sa.Times(ls_psit, g_wr)

pgwrt = arcpy.sa.Times(pgwr, arcpy.sa.Tan(phi_rad))

fw = arcpy.sa.Divide(pgwrt, h_sin_cos)Now we just have to put everything we have together. First we calculate γw / γr, then multiply it by ls_psit to get ψt in the numerator. Then we multiply by tan φ to get that in the numerator too. Now all we need is to get H * (sin θ) * (cos θ)in the denominator. Thankfully, we already calculated that in the previous step, so to get it in the denominator we can just divide byh_sin_cos. And then we’re done withFw!

Now for the last step.

# Step - calculate Fs

# REMINDER: where fs < 1, UNSAFE

fs = ff + fc - fwBoom! Easy as that.

Creating an ArcGIS Toolbox

Okay, so we did the legwork of calculating Fs for Collbran. But if we want to calculate Fs for different cities, we should turn it into a tool we can use with ArcMap. To do that, we need to make our own classes. Luckily, the syntax isn’t all that different from creating a function. You can see Esri’s toolbox template here.

class Toolbox(object):

"""

The class needed for importing as an ArcGIS toolbox.

"""

def __init__(self):

"""Toolbox class initialization"""

self.label = "Landslide Analysis"

self.alias = "Landslides"

self.tools = [CritRainThresh]Here Dr. Davis has just replaced the empty/default text with his own.

class CritRainThresh(object):

"""

Name: CritRainThresh

Features: Creates a factor of safety raster based on the Critical Rainfall

Threshold Model (Iverson, 2000)

History: VERSION 1.0

- initial attempt at an ArcGIS Toolbox

Ref: https://doi.org/10.1029/2000WR900090

"""

# \\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\\

# Class Initialization

# ////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

def __init__(self):

"""

Name: CritRainThresh.__init__

Inputs: None

Outputs: None

Features: Initialize the tool

"""

# ArcGIS Tool descriptors

self.label = "Critical Rainfall Threshold Model"

self.description = (

"Creates a factor of safety raster based on the Critical Rainfall "

"Threshold Model (Iverson, 2000)"

)

self.canRunInBackground = False

# Check that spatial analyst tools extension is enabled

arcpy.gp.checkOutExtension("spatial")

# Define constants and default values used in model

self.k_pi = 3.14159

self.deg2rad = self.k_pi / 180.0

self.gamma_r_nm3 = 20000.0 # unit weight of soil, N/m3

self.gamma_w_nm3 = 10000.0 # unit weight of water, N/m3Most of this is from our earlier script file. This stuff will happen every time you click on the tool in ArcPro, so don’t do anything that takes a long time in this. What we’re doing here is setting our constants that we used in the script file, making labels and documentation so people know what this is, and checking for the spatial analyst extension (because we’re going to use some of its methods). We’re also going to set self.canRunInBackground to False, because everything runs slower if you do background processing, and for our purposes, this is the end result of our project, so there wouldn’t be anything else we could work on while this is running.

First, we need to set our parameter info. We’re just going to get the parameters (a.k.a. arguments) that the user passes in as a list, and the only way we’ll figure out what’s what is by the list order. So we have to specify the order in which the user should give us the data.

def getParameterInfo(self):

[ ... documentation stuff ... ]

param0 = arcpy.Parameter(

displayName = "Hillslope raster (deg)",

name = "lands_theta",

datatype = "GPLayer",

parameterType = "Required",

direction = "Input"

)The getParameterInfo function tells the user what parameters they need to pass in, in order. This is an example for our first parameter. You may have noticed that it’s labeled param0. Computers like to start counting at 0 because that’s just how they roll.

displayName is what the user’s going to see, name is what you’re going to use, datatype is one of a number of types specified by ArcPy, and parameterType and direction are pretty self-explanatory—they set whether the param is mandatory or optional, and whether it’s input or output.

The other parameters are similar to this, so have a look at Dr. Davis’ toolbox file for the full function. Let’s skip to the end because it’s a little different.

# Set default soil moisture value (m)

param4.value = 0.2

param5 = arcpy.Parameter(

displayName = "Output factor of safety raster",

name = "outFs",

datatype = "DEFile",

parameterType = "Required",

direction = "Output"

)

# Send ArcGIS your parameters :)

params = [param0, param1, param2, param3, param4, param5]

return paramsparam4 is simple to set because it’s a constant, although we’re setting it as a parameter for now in case we want the user to be able to input it. param5 is similar to the others, but we need to specify where the user will store the output. Finally, we need to build a list of parameters to send to ArcPy. We already named everything in a nice easy way, so it’s intuitive to build the list and return it!

Hooray!

The execute method runs when you run your tool. So we should put all our calculations in here! First we need to load in our current map:

def execute(self, parameters, messages):

"""

Name: CritRainThresh.execute

Inputs: - list, list of ArcGIS Parameter objects (parameters)

- list?

Outputs: None.

Features: The ArcGIS toolbox tool execute function (i.e., Run)

"""

# Get pointers to the current project and map:

aprx = arcpy.mp.ArcGISProject("CURRENT")

map = aprx.activeMapThen, we need to get parameters:

# Get user-defined parameters by list order:

self.lands_theta = parameters[0].valueAsText

self.lands_phi = parameters[1].valueAsText

self.lands_c = parameters[2].valueAsText

self.lands_h = parameters[3].valueAsText

self.water_h = parameters[4].value

self.outFs = parameters[5].valueAsTextYou’ll notice that these are the parameters we specified in the getParameterInfo method. That’s why we needed to get that taken care of first.

# Create and initialize a step progressor to update the user

out_steps = 6

arcpy.SetProgressor(

"step", "Converting slope to radians...", 0, out_steps, 1

)This isn’t strictly necessary, but it’s a nice thing to do for the user. What we’re doing here is creating a progress display for the user so that they know what our tool is doing while it’s working. We have 6 steps, so we tell it that, and then we set a message to tell the user what we’re doing right now.

Speaking of which…

# Create radian version of slope

theta_rad = arcpy.sa.Times(self.lands_theta, self.deg2rad)

phi_rad = arcpy.sa.Times(self.lands_phi, self.deg2rad)This is basically copied from our other script, but we’ve changed k_pi / 180 into a constant. Most of the rest of this is just things copied from the script we wrote already, but with extra stuff like progress updates for the user. I’ll do one more section and then skip ahead—if you want the whole thing, check Dr. Davis’s file.

# Create Fc

arcpy.SetProgressorLabel("Calculating Fc...")

arcpy.SetProgressorPosition()

sin_cos = arcpy.sa.Times(

arcpy.sa.Sin(theta_rad), arcpy.sa.Cos(theta_rad))

# Get vertical component of soil depth (influenced by gravity)

big_z = arcpy.sa.Divide(self.lands_h, arcpy.sa.Cos(theta_rad))

h_sin_cos = arcpy.sa.Times(big_z, sin_cos)

c_gr = arcpy.sa.Divide(self.lands_c, self.gamma_r_nm3)

fc = arcpy.sa.Divide(c_gr, h_sin_cos)Again, mostly copied from our earlier script, but we use SetProgressorLabel and SetProgressorPosition to tell the user updates.

Skipping ahead…

# Save output raster

arcpy.SetProgressorLabel("Writing Fs to disk...")

arcpy.SetProgressorPosition()

fs.save(self.outFs)

arcpy.SetProgressorLabel("Complete!")

arcpy.ResetProgressor()

# Add raster to current map

map.addDataFromPath(self.outFs)This is the last thing we have to do. We didn’t actually save anything in our old script, so we can do that by calling the aptly-named save method!

How convenient.

Then we tell the user we’re done, and add the finished raster to the map! And that’s it! We’re done. For the rest of the functions, we can just leave them all like they were in the template! So we’re done! Hope you learned something.